Featured by ARTSY: A Journey to Mexico with Sarah Lucas, Through the Eyes of Collaborator and Partner Julian Simmons.

Featured by ARTSY: A Journey to Mexico with Sarah Lucas, Through the Eyes of Collaborator and Partner Julian Simmons.

‘…we asked the photographer to share insights around the images, the trip to Mexico, and his multivalent relationship with Lucas’…

The unedited Q&A here…

How did you first meet Sarah Lucas?

Legal squatting.

ICH …Islington Community Housing – a co-op of near-derelict houses waiting for an uncertain period before improvement. The deal was we paid a low rent and kept the places warm and occupied – but might have to move out the next day.

Sarah was living on the first floor – above, I was living on the ground-floor with a girlfriend – who is still a good friend to us both. It must have been around 1993-95, while I was a B.A. student building computerised drawing machines. I remember getting out of the bath – a shared bath for the whole four-story house, and being locked-out of the flat downstairs, so having to knock on Sarah’s door for the front door key, I presume I had a towel.

We still refer to something or some-such as being ‘very ICH’, meaning slightly ad-hoc, home-made, rough and ready, a real and ingenious solution, certainly working more than well enough, and with enjoyable quirks.

‘Very back of the van’ is another, similar, but more compact version of very ICH.

How long have you been working together?

Since we’ve been living together, 2008; in fact since 2007 when we found prehistoric butter.

Shortly after we started to live in deepest Suffolk, one winter when the heating-oil ran out, and the oil truck couldn’t get down the iced-up track, we fired-up a neglected Rayburn stove in the kitchen, shut the doors, got really hot, stripped off, I slapped my nob on the table – and Sarah started making a mold with plaster bandage.

Actually we’d been on an Early-Man trip in 2007. Sleeping in the back of my old ex-Gulf-War 110 Land Rover – ‘the van’ for a few weeks; noisy, leaky, smelly, heading up Scotland’s west-coast with a replenishing bottle of whisky (I’ve since given the LR to a project in Uganda). I’d improved it – been under it covered in black oil, and sprayed the body in a particular ratio of yellow and black paint – which makes green, matte of course – it blended in – unlike gloss it got darker when it rained. The notches cut into the steering-wheel – I can’t tell you about, except they are brutally real (from the war).

A blow-up bed stashed on the left, knickers drying up on the right, all strapped with bungee cords, food on the side-benches, us sleeping squeezed between on Jacob sheep-skins; lots of roof-dripping condensation. By the way, that’s not a sun-roof at the front, it’s a military escape-hatch.

We had the shared notion – from William Blake – that the ‘North is the Imagination’. “Are you sure you know what you’re doing?” – advice at the time was this would surely break apart any relationship; it didn’t, we knew what we were doing, and still do.

Anyway we ferried over to Orkney then Shetland then Yell then Unst – the weirdest mentally crazy and most northerly point of British Isles. Unsettlingly the ferry was free on the way over – was there no return? – that evening I made sure we were on the last ferry back.

Along the way on Shetland we’d seen a massive cube of butter in an Early-Man museum, hidden and preserved for a few thousand years. Here it was, dug-up, more than a foot square – perhaps two foot square, real value. We stood in front of it, for an eternity, saying nothing, all telepathy; of course it was slightly dirty, but it was butter – a block of it, the work of a few thousand udders I suppose. Sarah said what most fascinated her school-days was Early-Man, shame he’s mostly overlooked these days. Early-Man was on our agenda from the start – how he found beauty in rude materials to hand.

So along with casts of my nob, were broken flints and antler-like branches collected from the fields. This was the body of work which became the exhibition Penetralia.

What draws you to her work?

She does.

People draw me to their work, but which I mean everyone, not just artists.

Most art turns me away – demanding either spiritual worthiness, or worthiness through the hard-work and time it took to make, or pushing hardship and pain like an indulgent charity advert; hers’ doesn’t – it speaks of transformation. Uplift is a great course – like a great morning …and a building site.

I’m not so interested in contemporary art (contemporary as in the last thousand years). Sarah likewise. In fact as artists we make work because we cant find it elsewhere, and we require it.

She’s certainly one of the most profound artists, working today, and from whenever. It’s not at all art just for the establishment, it’s for elevating everyone.

How did your involvement in the trip to Mexico come about?

Dad.

Depends on how far to go back – how many shoulders to stand upon, but basically dad. He had a collection of ancient anthropomorphic south-American stirrup pots, Moche maybe, black-clay. There were several examples in Anahuacalli, they stood out, in a familiar way, home from home, and there were variants still being made in the Oaxaca valley from the local black-clay.

Another answer might be Don Juan (through Castaneda).

Possibly you’re enquiring more of the immediate. The proposition was put to Sarah for a show in Mexico city. Since previously living, making, and installing a show in New Zealand – a 5 week trip, she’d held to the idea of living, making work, and exhibiting in places we’d never been before.

So Mexico was a yes, though we both wanted to work outside of the city, and actually in this case Sarah wanted to show outside of the gallery context. Once José of the Kurimanzutto gallery got the measure of this, our trip was organised into making the work in Oaxaca, and showing it Diego Rivera’s studio and extraordinary temple to pre-Hispanic art.

Photographing the works and designing a catalogue was my principal task, but also in whatever way assisting Sarah in making the sculptures and drawings. In fact I went out to Mexico with ‘InDesign’ so as to present the final catalogue ready for print just before we would leave. As it turned out the intensity and amount of work meant the catalogue – or as it became the tome, was published a year later.

Can you tell us a bit about the trip?

Can you tell us a bit about the trip?

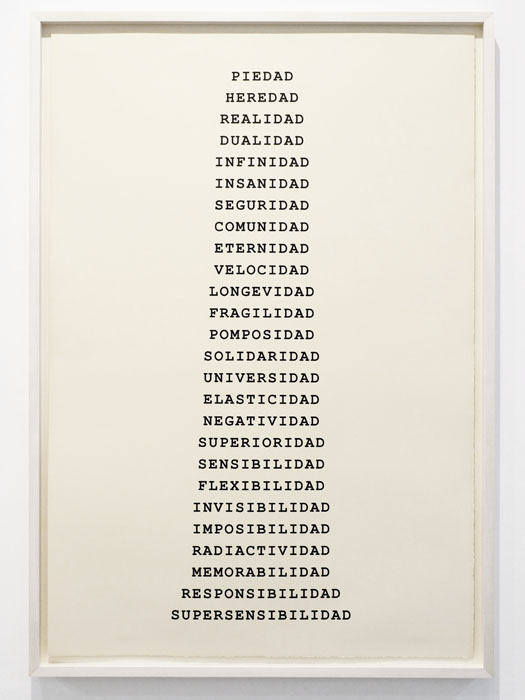

It’s an exemplar of Realidad.

The DAD LIST is the new way to learn Spanish, it’s a lighthouse.

TITTIPUSSIDAD tells the whole story.

How long were you there?

Before and after the resurrection.

3 weeks in Oaxaca over Easter (music in the streets, fireworks while church services were being held, a burning man), and 1 week either side in Mexico City, 5 weeks in all… …that’s over 80 erections in all, including Maradona and Dr Atl.

Where were you living and working?

Same place, as is always the case.

Sarah for the most part has lived and worked in the same place, at home. It’s been the same for myself, the ability to work at odd hours, and to have everyday life in the background /or foreground, helps, not always, but generally it’s preferable to having a studio divorced from life ( – as if art is in some way separate from life!).

Initially we were to live in a hovel in the hills around the Oaxaca valley. We unpacked and everything, the sun set, and we attempted to get into an unfeasible bed, rickety, about to collapse. The hovel had an en-suite compost toilet full to the rim with shit. I think who’d found the place was following the notion that we like to work in a rural situation, rather slap bang in a noisy city. Anyway the ammonia stench was too repulsive, along with the hovel being entirely unlivable, every surface sticky, and the cooker didn’t work, but it was the overriding stench of shit and ammonia that kept us awake that first and only night. A couple of days later we moved into a house in Oaxaca, with a shaded terrace surrounding a patch of garden, the perfect situation to live and work.

Can you share any memorable anecdotes that capture the spirit of the trip?

The Holy Shit Mountain.

We planned to place it on a wooden board and parade it around the streets as a holy relic, unfortunately we couldn’t stay, so the mountain and its holiness remains a legend.

Black feet. The heat was insane, on occasion I’d be working entirely naked, which was novel when we had visitors! In any case we all had bare feet – it wouldn’t take long before we had black feet, soot from Popocatépetl, the local active volcano.

We bought all of the Delicados cigarettes in Oaxaca. A few thousand.

Mezcal, it’s psychotropic.

But in many ways the whole trip was an anecdote entitled Realidad.

Did you plan the way these photographs would document the trip and Lucas’s process or was it more organic?

Mainly to avoid photographing Sarah working.

Apparently even on a quantum level, observation changes the outcome. Everything is recorded, even looking; I didn’t want my photographing of Sarah working to in any way disrupt her process – and so change it. Of course everything has an impact, but I didn’t want my photography to impact on her making.

I knew I wanted to make a book documenting the trip; in terms of planning I had it in mind to photograph all sides of the sculptures, and that all those views would be in the book – in a way very classic, something of a museum – not in a preservation way, but in terms that photographs are living muses.

Apart from that, early on while in Oaxaca I found a white-ish wall that would work as a backdrop, sheltered from the evening rain storms, built a stack of blocks up, and so made a ready spot for photographing the sculptures.

Some of the photographs have been described as “portraits of Lucas’ sculptures”—is that what you intended?

No, but that’s probably a limitation of language in describing the image.

Portraits in terms of portrayal, would be aiming for a representation. The ‘final’ images, which importantly in this case I printed myself, should have as much individual power as beholding the sculpture. Indeed I hope the images in some way, sum the various powers of the sculpture into a didactic single power.

Images – a notion which needs re-understanding, are already present in the original sculptures – nothing is without an image. Indeed I believe the image is ‘a priori’ to the object, in many ways the sculpture is a manifestation of the image.

It is these images which I endeavour to maintain and intensify.

What was your process like in capturing these “portraits”?

Casual.

I can work with any equipment, but have to shoot handheld. Of course we all see the world through a lens: a head-held lens, my practise just adds another lens, and that’s it. The mind behind is the most significant import.

Although as a point of technical process… I always use a standard zoom lens. Most often this is avoided by professionals – I think for absolute resolution reasons. I use a zoom to control perspective – to control the scale of the foreground in relation to the scale of the background; it’s a perspective control device. You’ll know this from the film Vertigo, but in terms of still photography it enables either hiding or revealing parts of the background obscured by the subject – actually looking around behind it, in a way the unadorned eye cannot. Nothing to do with zooming in.

Prime (fixed focal length) lenses are ok – engaging with the mind in a single dimension; properly understanding a zoom in terms of perspective control, adds complex control to spatial dimension. Of course this process is in the taking – not in viewing the image …though I trust in gazing at the printed image this considered notion of scale over spatial distance will be evident, and is why I mention it.

Indeed.

What are the challenges you faced in photographing Lucas’s works?

Chilli, constant gut inflammation.

It was impossible to avoid eating chilli, I had constant gut pains. The sun, burning god-like heat, sweating.

Mexico City, Anahuacalli – where the works were installed, was like being inside a geological volcanic magma chamber, extraordinarily dark, black as hell; that was the only real practical challenge – in terms of photography, and of course by that time the gut spasms were at their maximum. In a land of volcanoes, earthquakes and electrical storms, gut-inflammation was I assured myself part of the old-god intensity: challenge is an extreme curiosity.

What is her process like?

Fast, to-hand, engaging, craftsmanship.

In Oaxaca much of the process started in the head, particularly over the first few hours of every morning, we’d drink coffee and talk how the day might proceed in relation to the previous, or what the show might be requiring; every day a fresh challenge, finding out a new, not a job of work. By the time other people might arrive at the house, around midday, we’d start drinking beer; gradually we moderated this slightly, but still produced piles of beer bottles.

Actually it often starts with materials, it helps the mind to have something to mull upon, and move about: imagination is like the abstract, it doesn’t arrive from thin air, it’s from the concrete. So having some toilets (the ‘pans’) knocking around helped enormously.

Can you talk us through one of the photographs in the show and its significance to you?

Can you talk us through one of the photographs in the show and its significance to you?

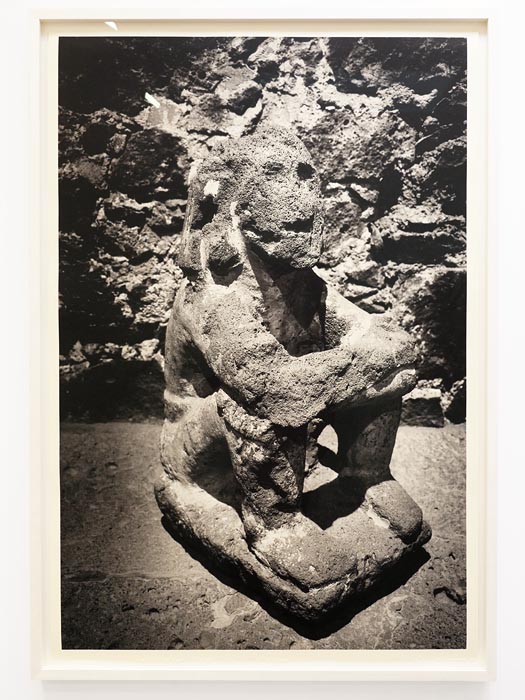

Xochipilli, he’s where it all started.

I saw him in Anahuacalli on a recce before we flew down to Oaxaca. He’s one of the old gods, a pre-Hispanic sculpture. Xochipilli is ‘the Prince of Flowers’; flowers – which by the way, include hallucinogens.

He’s a child, gentle, open-eyed, but he’s also a teacher. Sarah arrived in Mexico thinking she would make a NUDS show; after a few smokes, Realidad was born. The previous tightly wrapped NUDS suddenly became more humanly present, and as forms more open.

Realidad was the first of the anthropomorphic NUDS, the first to incorporate a backbone. When Realidad was placed in Anahuacalli, he gazed towards Xochipilli, and they caught up on the last few thousand years.

What does it mean to you to have these works presented in a gallery?

People I don’t know can see them – in the flesh.

Maybe it’s because galleries are becoming larger, more tank-like, more morgue-like, that I generally don’t take much pleasure in seeing art in galleries.

I prefer to come across art either in private homes or out in public environments – with it’s owner (which may be the public); to see how it has integrated into life, and elevated it.

Actually the great thing about Paul Stolper’s gallery is it has the architecture and proportions of a house, it’s human before humans occupy it. It has the British Museum – a somewhat giant ferry moored at the end of the street, a fish & chip shop to the right, and a pub serving Aspall to the left.

Again that was partly why Anahuacalli was so perfect, it wasn’t a bright, bleak gallery, in fact quite the opposite, it was dark and crammed with weirdos ( – of the clay-pot variety).

How might they be read differently in the gallery exhibition as opposed to within TITTIPUSSIDAD?

Fine presence (though TITTIPUSSIDAD is already supremely present).

I printed the works myself, in a manner I’ve been developing for many years to achieve the greatest power of image. Part of this necessarily is the witness; I have a thesis that powerful images are created by the witness being in a position of some terror – this distance enables the image to elevate the witness (R.M.Rilke springs to mind). If the image is too friendly and close, it can’t take the witness anywhere, indeed it might even drag an already somewhat elevated witness down.

Are you willing to make the journey? An unfamiliar slightly unsettling appearance, if confident, is in someway able to encourage the viewer to ‘make the journey’, and behold with a novel heightened awareness. Presences elsewhere that might previously have gone unnoticed, now leap forward; the newly installed perception makes the once invisible now familiar and fundamental. This may sound like a peculiarly esoteric proposition, but I think it to be very primitive and basic – like war, god, and sex.

If there is something that can heighten perception, and elevate thought, surely the artist should be aiming to propagate and project that.